Don’t expect a Comeback Kid comeback in Tauranga

Tauranga is not Northland, it is not 2015, and National will win Tauranga – with or without Winston Peters gearing up for one last big score.

Simon Bridges has resigned. This should not have been a surprise. With Christopher Luxon consolidating the National vote, Bridges’ chances of using chaos as a ladder have evaporated. Maybe there’s some terrible scandal waiting to break. Maybe he jumped, maybe he was pushed.

It all scarcely matters at this point. He’s off to enjoy the board-appointed retirement benefits former leaders of the party of capital are entitled to.

Don’t let the door hit you on the way out etc. etc. etc.

By-election prospects

So the rest of us get to have a by-election. To give you the tl;dr version: whatever TERF-bangs evangelical real estate agent or suit-filling agribusiness scion National end up selecting is going to win.

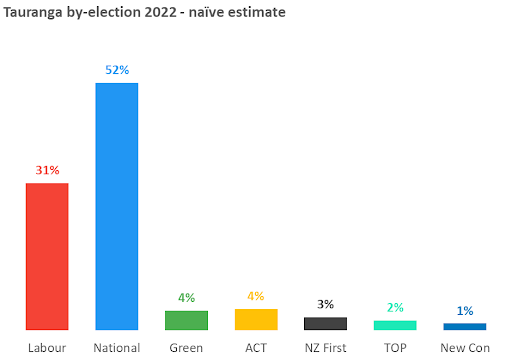

Generic candidate model, assumes no Winston Peters

By-elections have a reputation for being sui generis. Wacky and unpredictable. Novelty candidates can make them wacky; but they’re usually predictable. Looking at recent polling, adjusting for local conditions, and accounting for historic candidate preferences gives a decent baseline of what to expect. Not a perfect one, but still better than unconstrained punditry.

The polls

It got lost in the denial stage of the centre/left grieving process, but the improvement in National’s fortunes since late last year is a phase-shift on a par with Ardern’s ascension or the initial COVID wave. This is slightly off-topic, but Labour’s slide has been constant pre- and post-Luxon if you wanted my thoughts on Luxmentum versus a Jacindive.

The poll’s life has entered a new phase

We’re a long way from 2020, when nationwide conditions meant Labour were competitive even in Tauranga. At the vertiginous heights of 60%, they were odds-on favourites for an upset. Even the 50% they hit in the election was good enough to put them within a 2% swing of victory. Barring a catastrophic change on the order of the 2020 COVID bump, the poor time-serving party hack Labour will inevitably throw under this bus has a snowball’s chance.

Looking at Peters’ prospects, general polling conditions matter less than the other effects below, but New Zealand First putting up ones and twos is worse than the sixes and sevens they were pulling before the Northland by-election in 2015.

Local conditions

Tauranga – famous for being God’s waiting room (3rd= in terms of population over 65) – is unsurprisingly a conservative electorate. However, the exact kind of conservative has changed over time. It was once the capital of Winstonland. New Zealand First ran +12% ahead of the rest of the country. Now, it looks like your standard affluent Tory seat (this is unusual for a medium-sized urban centre). As of 2020, National is at +7% and even ACT makes a +1% showing.

🐟🐟🐟

Adding polls and local conditions together, at this point Tauranga is safely back home with National, at least in terms of the party vote.

Vote splitting

To get the candidate vote from the party vote, we have to factor in vote-splitting behaviour. Vote splitting is normally consistent within seats across time when looking at general elections. Helpfully, the pattern also seems to hold for by-election results.

For Tauranga in 2020 those preferences were unremarkable. Major party voters vastly preferred their own parties’ candidates. Green and ACT voters prefer the relevant major party candidates, albeit at a lower rate. In absolute terms, the other minor parties weren’t significant enough to have a decisive effect.

Flipping to a candidate view, multiplying all that out with current party preferences, then stacking up candidate votes from each party’s voters, you get a result that looks something like this:

But does it work?

This approach performs well historically. It would have picked the winner in all but one comparable past by-election and does okay on picking margins. It’s a little over-baked and misses turn-out and ‘candidate quality’ (whatever that means). But it gives a solid framework for thinking critically about what might happen once writs for Tauranga are called.

Te Tai Hauauru (2004) and Te Tai Tokerau (2013) were excluded as there was no historic data for the newly formed Māori or Mana Parties. Taranaki King-Country (1998) predates the release of vote splitting data.

If everyone runs a generic candidate, a National victory is essentially inevitable. If ACT and the Greens choose to run candidates, expect them to run a little worse than they would in a general election. An FPP format and low turn-out usually aren’t kind to minor parties (with some exceptions - like Russell Norman in Mt Albert in 2009). The incumbent party’s candidate could also do slightly worse, as they won’t benefit from the name recognition the outgoing candidate received.

But what if not everyone runs a generic candidate? What if we throw in New Zealand politics’ most notorious wildcard?

The glaring exception to the tidy story above is Peters’ Northland run in 2015. It was a genuine upset, the first one since Social Credit did for Don Brash in 1980. Tauranga is Peters’ old stomping ground, so naturally enough people are speculating whether we could see a repeat.

What about Winston?

Tauranga has (or had) similarities to Northland. Both have favoured New Zealand First historically. However, Tauranga has trended away from them long-term. More concerningly for Peters’ chances though, is Tauranga’s much more pronounced pro-National lean.

The problem really starts to show once you compare estimates of 2015 Northland party preferences with 2022 Tauranga ones. If Peters runs, he’ll be starting 8% behind in terms of reliable New Zealand First voters.

Those are all votes he’ll need to pick up off other parties’ voters. This brings us to Peters’ most serious problem: vengeful National voters.

Given 2015 was a by-election, we don’t have data on where Peters’ votes came from. It’s safe to say though that – in addition to New Zealand First voters and Labour/Green voters keen on giving John Key a bloody nose – his victory relied on a fair portion of voters who otherwise preferred a National government. The results from 2017 (where fellow mandate-protest coddling crank Matt King edged Peters out) give a clue at what was going on two years prior.

Even winning over 19% of National voters (a quarter of ACT voters, and a full third of New Conservatives) wasn’t good enough for a win. Switching to look at Peters’ history in Tauranga, the odds of him approaching anything like 19% seem pretty slim.

Following Peters’ decision to prop up the final term of the Clark government in 2005, right-aligned voters abandoned him. Even in 2005, winning 25% of National voters wasn’t enough to beat Left-Bollock Bob Clarkson. It would take ten years, a new government, and a new electorate for them to come back.

Tying this all together, even under best-case assumptions where Peters does as well as he did in Northland, he’s still a full 13% short of victory. It’s been 20 years since Peters last won in Tauranga. The seat has changed, the voters have changed.

Sorry koro, not this time.

Peters will probably still run. Politically and psychologically, he needs the attention. Three months of consequence-free grandstanding with a nationwide audience is too good a chance to pass-up.

Future leaders – an aside

A random observation from researching this: by-elections in the MMP era have a pattern of producing future leaders – one Prime Minister (Ardern), one party leader (Shearer), five Ministers (Turia, Faafoi, Whaitiri, Williams, and Wood), and one chaotic abusive mess (Lee-Ross).

So expect drama, expect horse-race hype, and maybe expect great or terrible things of the winner.

Just don’t expect to be surprised.

Rustie tweets about politics and Wellington